I was told, but am not 100% certain if it’s accurate, that this issue broke sales records held by the magazine since their 1970 coverage of the Mai Lai Massacre.

It was translated and published in over 26 countries.

I never asked O.J: “Did you do it?”

I just let him talk.

A bit of background

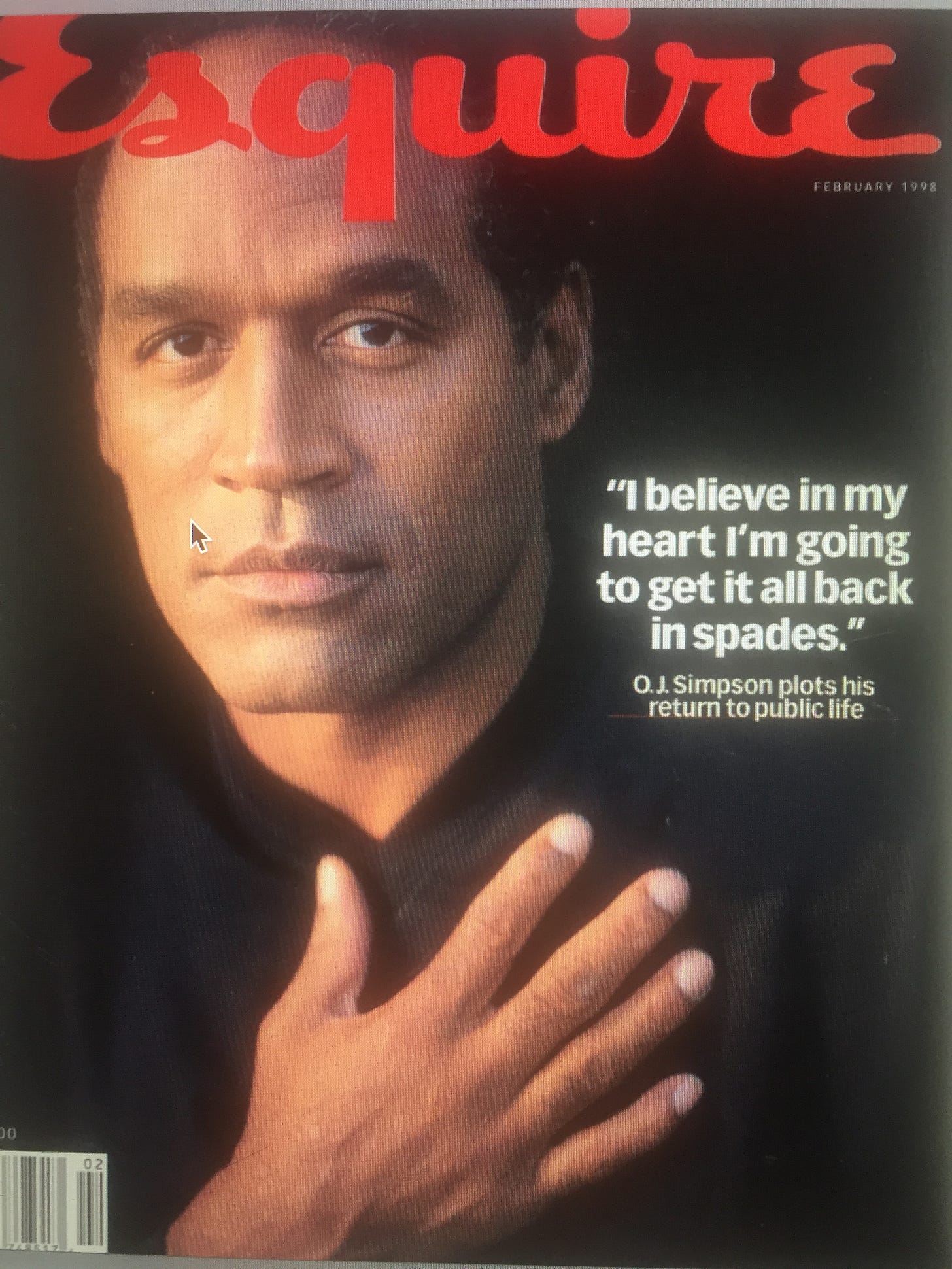

Then Esquire editor Bill Tonelli—a great editor— commissioned this piece to me in 1997.

It was published to great fanfare in the Feb. 1998 issue, just before the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke.

The Phone Call

O.J. had called me at home in New York, following my return from months of desperate searching, in Los Angeles, and after a rambling interview I’d finally managed to arrange with him. (Documented in the article.)

When O.J. called me at home that night, it was to let me know he was not “done” talking to me.

“I don’t know why, but I talk to you like you’re my shrink or something,” he said, as I searched for pen and paper.

Then he said the famous words: “Let’s say I did it. If I killed her, it would have to have been because I loved her very much, right?”

Stunned, I wrote the words down with a blunted pencil, and the feeling I had was dread. If my journalistic ambition was more intact I’d have been thrilled for the scoop. But I was accustomed to interviewing pariah scientists nobody cared about, which suited me as an introvert. Now I would have to navigate a bonafide media circus.

I knew O.J. was intending (obviously) for me to quote him. I knew how it would be interpreted. I knew I didn’t have a recording. And I knew it would be a media storm.

I emailed my editor, Peter Griffin (Tonelli had since been let go in a mass Esquire firing/changing of the guards,) and I said I had good news and bad news. The good news was the quote itself, which was not a “confession,” but would certainly re-imagine the piece. The bad news was, he would have to take my word for it, as I had no recording of the phone call.

Esquire’s fact checker at the time was a charming fellow named Andrew, who smoked Marlboro Reds, and used to call me “toots.”

“Toots,” he said, the next day, “tape recorders are over rated.”

I laughed, with relief. Never met a classier fact checker.

They believed me, and we worked together as a team.

I asked for the quote to close the piece. They wanted to put it on the cover.

We met half way—my editor worked it into the lede.

When the article hit the stands, media around the world made it front page headlines, as far afield as mainland China, and my hometown paper in Örebro, Sweden.

The day it hit, I got lucky again: O.J. called my editor, Peter Griffin, in New York, and said: “What are they freaking out about?” And he repeated the quote verbatim.

I could have been lynched for inventing a quote—but he saved me.

I have never known how to describe this, but I felt I must not accuse Simpson, or “throw him under the bus,” which was born out of my own pariah status—sympathy for a fellow pariah. Even PCR inventor, Kary Mullis, who was supposed to testify for the Dream Team about the DNA (which he felt was “a subjective science” as he later told me) was too controversial, for his HIV denial, and never did take the stand.

Esquire tried to train me, in a Hearst media training basement fitted with TV cameras and interview chairs, to display more animosity toward Simpson, but soon discovered I just didn’t have it in me. They finally decided to only let me do a small handful of interviews: The Today Show, CNN, Keith Olberman at MSNBC and one more I can’t remember.

I was a dud in the sense that I refused to say Simpson had confessed, only that it was a cryptic line. Admittedly.

After they pulled me, angry man-pundits like Geraldo Rivera, and various TV psychiatrists had a real go at me, accusing me of having a “school girl crush” on O.J. That followed me around for years, that accusation. When I was interviewed for that documentary that got an academy award, O.J. Made In America, the director ended the several hour long interview by shouting at me that I was in love with O.J. and whatever.

A few months ago a producer called me to ask if I would be interviewed for a TV series on the something or other anniversary coming up in June, and I explained that I really hate talking about this. Then I tried to interest her in the Prozac angle, and felt a familiar dead silence on the other end of the phone.

The Things We Remember

When my agent called me that evening in 1997, she said, sounding bored: “Esquire called. I’ll tell you what they want to assign, but you won’t want to do it… It’s an article about O.J. Simpson’s post-trial life, as a pariah in Brentwood.”

“Bonnie,” I asked, “why would I not want to do that? Please set up the meeting.”

She meant that nobody in acceptable society would want to talk to O.J. Simpson. I had these antiquated notions that any journalist would want such an assignment. But I didn’t approach him with the requisite “I know you did it” hostility. I left that to the various, endless lawyers. I was also expected to take such tones “as a woman,” but I couldn’t do that either. People used to scream at me at dinner parties that I should have gotten my head chopped off too. People wanted to know if I wasn’t “afraid he would kill me too.”

“Of course not,” I said. “Why on earth would he kill me?”

It was hysteria, American style, and if I may: Racist. I don’t use that word often, but the O.J. story was truly and wildly infused with racism, pretending to me umbrage over a double homicide.

If we “cared” about homicide in this country, we would talk about the Clintons, before we got around to O.J. And before we talked about the Clintons, we would talk about Pharma.

We don’t care about murder. Except in rare cases.

Lydia and Mike

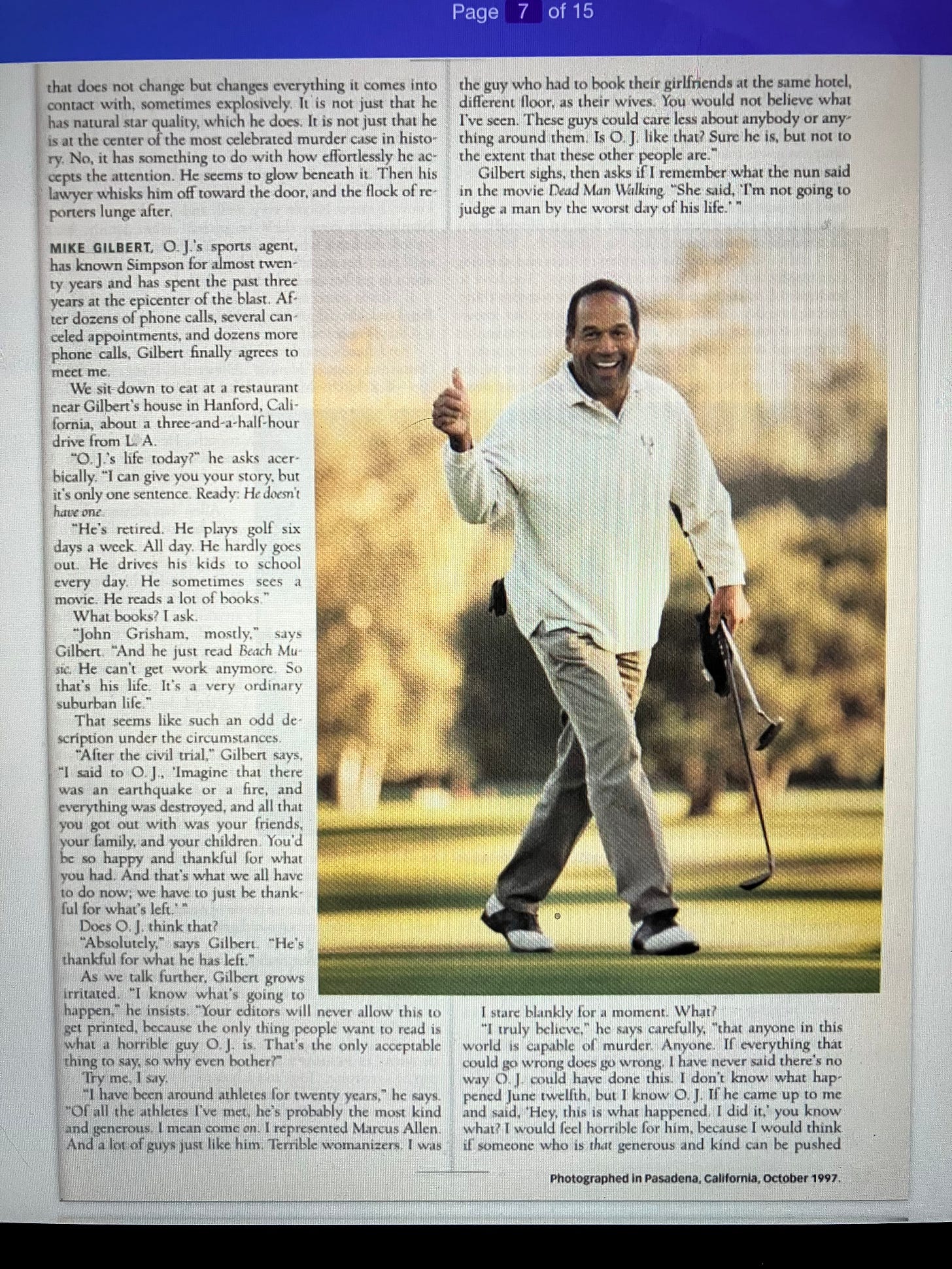

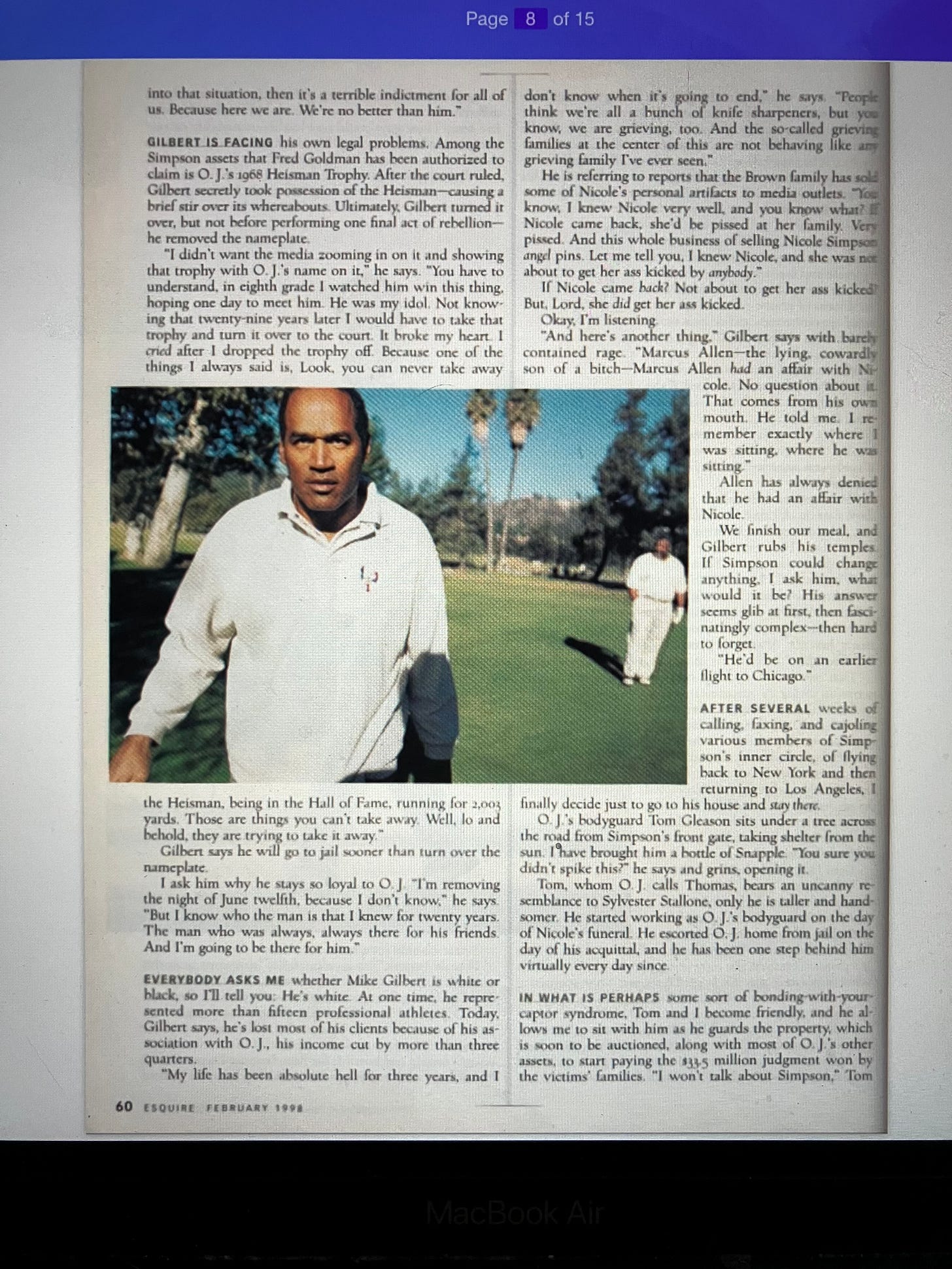

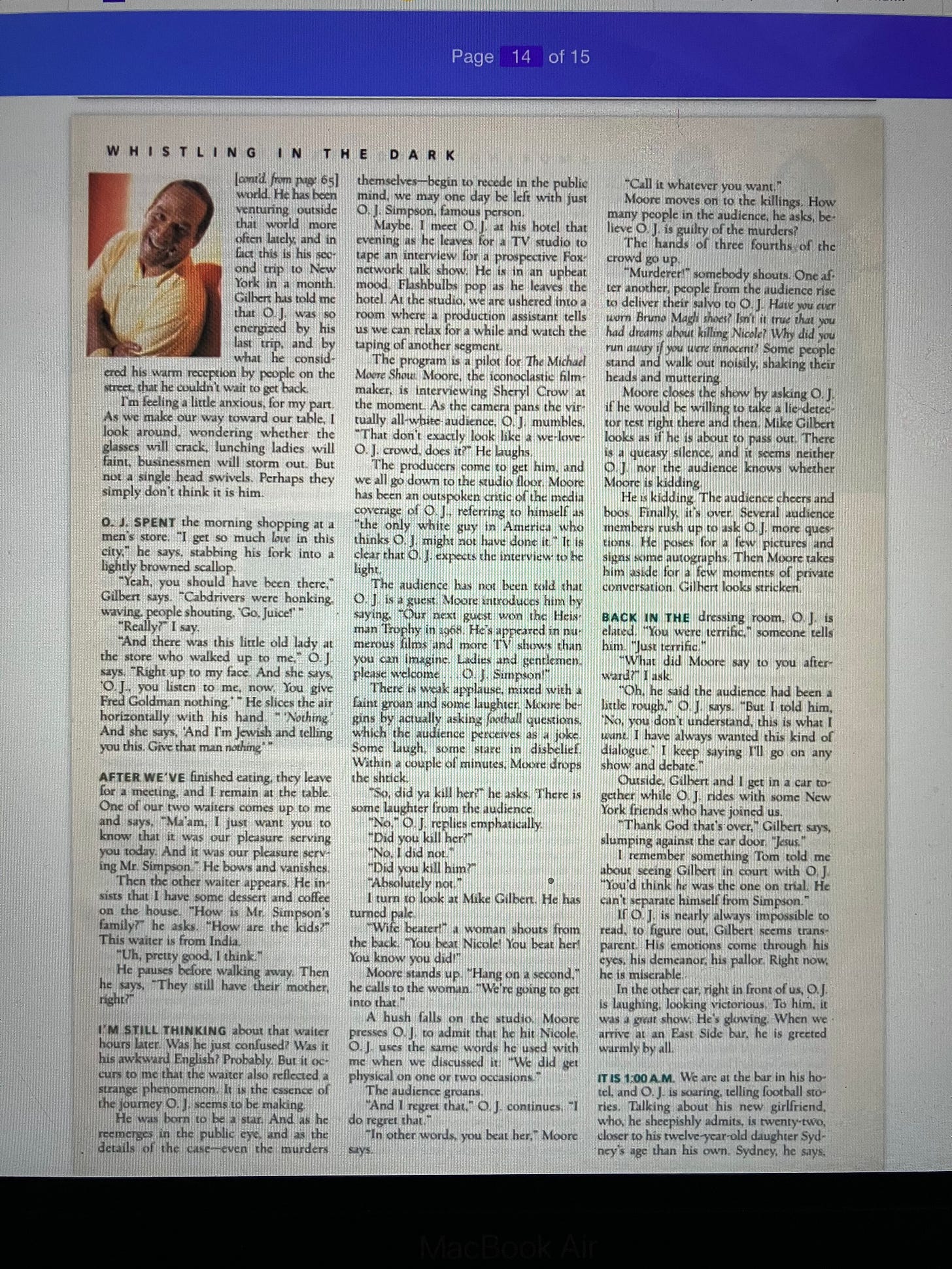

I owed my success here in large part to a woman named Lydia Boyle, who got me in touch with Simpson insider, and memorabilia agent, Mike Gilbert, whose book I later ghost wrote. Mike is the tragic narrator, the real soul of the story, with his inability to let go of his one time hero, friend, and client, at odds with his feelings of guilt toward the victims.

The O.J. commentariat, the endless lawyers and pundits who minted millions—they had never gotten dirty, never gone to the inner circle. That’s why this piece stood apart. Because of Lydia, because of Mike, I gained entree into the inner circle.

I never wrote for Esquire again, (though we remained on good terms, and they sent me yellow roses after the piece came out.)

Prozac?

After the article was published, Gilbert told me O.J. was on Prozac at the time of the murders, and that his personality changes had been so severe in the weeks before, none of the inner circle even believed it was he on the phone. He was certain Prozac was the catalyst, and certain O.J. was the guilty culprit (which I never took a clear stance on.)

Bill Tonelli later commissioned me to write another O.J. article for Rolling Stone, where he landed, after Esquire, called “O.J. Inc” in 2000. In that piece, I fought tooth and nail and the Prozac fact (which I’d confirmed via O.J’s psychiatrist) made a vanishing appearance in one sentence. That article is no longer available online, even at Rolling Stone. If I find it, and publish it, it will be the first content I place behind a paywall. (My paid subscribers have been polite enough never to complain they get no exclusive content.)

Bill Tonelli was excellent, as were all the staff at Esquire.

If I have a confession, it’s that I came into this story with a gash wound inflicted by a Federal Court trial I can’t get into now, but it was aimed at ending me once and for all. I was down to 98 pounds after three years, and it had just ended when my agent called me that night.

I have always believed the pharmaceutical industry paid for that lawsuit.

Monster Making Inc.

O.J. later said I was one of only three reporters he would speak to again—that he trusted. The other two were Linda Deutsch of AP, and Greta Van Susteren. I know his vote of confidence is not something many people would be proud of. But what it means to me is that I at least didn’t take the easy road, of bashing The Monster when the bashing was easy and rewarded.

O.J. was the monster, for years, as Trump became later. America likes to designate one monster—per epoch. Or, as Rene Girard would say, one scapegoat.

It makes me sad to think back on all this.

It’s a profound tragedy, implicating and engulfing us all, somehow.

And who are we to say whether he loved her? Why do we presume to speak like this about other people? Why are we so hard and judgmental, so disinterested in what makes people do things?

I KNOW there are angles and stories and avenues suggesting Simpson’s innocence; I’m agnostic. I’m looking at us.

The DNA evidence may be “overwhelming,” but the story—the crime itself, in essence—was in my opinion never solved.

Over the years, I stopped talking about O.J. and Prozac.

Maybe it was just a pet theory—a way for me to assuage my own guilt over being too “kind” to O.J. despite his well documented physical abuse of Nicole.

I felt sorry for him. And her. And their kids. And her family. And the Goldmans.

If you look at the Tweets about Simpson’s death, your will notice a certain ice cold insensitivity toward all involved.

Crass jokes.

The story will never be anything except an unseemly place where Americans turn a buck, get rich, pretending to me moral, ignoring the nuances, and above all—our own shadow.

—-Celia Farber

Additional material:

O.J. did take the Covid vaccine(s) and even did some moralizing:

Clip here.

He died of cancer, at 76.

Here’s a link to an online version of the article, full of ads, and without Gregory Heisler’s photography:

Whistling In The Dark, Esquire

This is such a terrific piece. I can't exactly put my finger on it but it just brings me back to worlds & ways of looking & writing about things that have just disappeared.

Celia, you stand out for your refusal to vilify appointed monsters. If only all journalists were as rebellious, contrarian and committed to truth as you. I predict your post with be the very best commentary ever to be written on OJ's death. I was yearning for a book, you're that good.