Were Lennart Nilsson's Iconic, World Famous Photos Of Fetuses In The Womb…Photographed In Glass Jars? Guess Who Says Yes? Sweden's Leading Newspaper, In A Profile Of His Archivist And Stepdaughter

Part 1 Of a 3 Part Series Exploring How Early Progressive Abortion Laws In Sweden Led To A Crisis Of How To Produce Research From The Aborted Fetuses. Lennart Nilsson Was Invited In To Document It.

The story I tell here is one that broke in May of 2024, at SVD newspaper, in Sweden by Kristina Lindh, titled: “The Truth About Lennart Nilsson’s Photographs.”

It was a story that broke in a kind of controlled demolition way in Sweden, and as far as I can tell, not at all anywhere else.

I first saw the story on the FB page of Bobbo Sundgren, when I wrote about his son’s death by Moderna shots, in June.

I remember being dumbstruck.

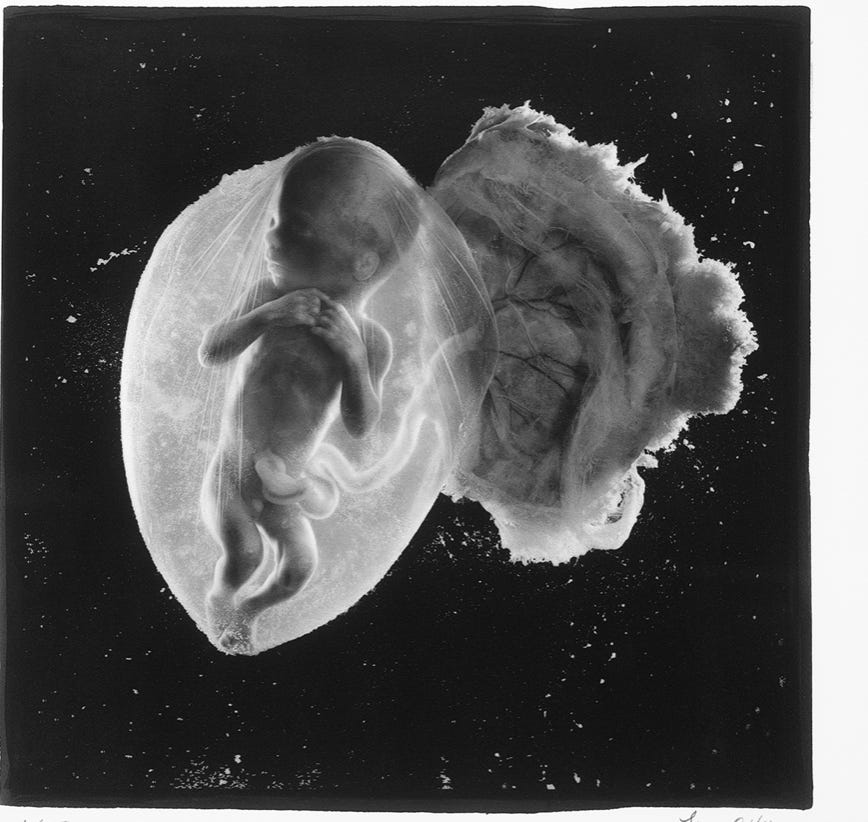

Bobbo had posted an article from SVD that revealed that the famous Swedish photographer Lennart Nilsson, whose “A Child Is Born” embryo photos became an international sensation, had not, in fact, magically photographed gestating fetuses. Rather, Nilsson photographed dying and dead embryos, that had been removed by a special c-section like technique in a Sweden where abortion laws had recently been relaxed, and (anti-abortion) doctors wanted the matter documented. This was in the 1950s.

The post aborted fetuses were placed in glass vats, that were lit up from many angles, creating the iconic Nilsson photographs the entire world looked at as images of life, beauty, hope, and God’s creation.

Were none of them alive?

At best, some are within the last few moments of life, kept alive in the vats while Nilsson made his creations. It is believed he even manipulated the baby sucking its thumb.

Here is an outtake from the Wikipedia page for A Child Is Born:

”The images played an important role in debates about abortion and the beginning of human life.[16] Nilsson himself declined to comment on the origins of some of the photographs' subjects, which in fact included many images of terminated and miscarried fetuses:[5] all but one of the images that appeared in Life were of fetuses that had been surgically removed from the womb.[15]”

That last line: “All but one of the images. that appeared in Life were of fetuses that had been surgically removed from the womb.”

Did we know this?

No—absolutely not.

I also question the “one.”

If you check the footnote to this bombshell sentence, you learn that The University Of Cambridge actually published something on the story all the way back in 2000. But it did not “detonate.” Why is Sweden coming clean now? That is a fascinating sub-story, captured by Kristina Lindh in SVD (translated below.)

I’ve had a long time now, to think about this story, which I pushed to the side countless times.

A writer has to think: “What story am I telling, and why?”

A Swedish friend barely batted an eyelid when I told him. “Jaha,” he said, laconically. But he’s on the inside, and hard to shock.

This morning, a British friend said, after a long pause: “It’s kind of Satanic actually.”

We discussed what that might mean, “Satanic.” Not a word most people would normally associate with Sweden.

I pressed her a bit, as to how she defined that word.

She said: “To present something people think is beautiful and wonderful, and it’s actually the opposite.”

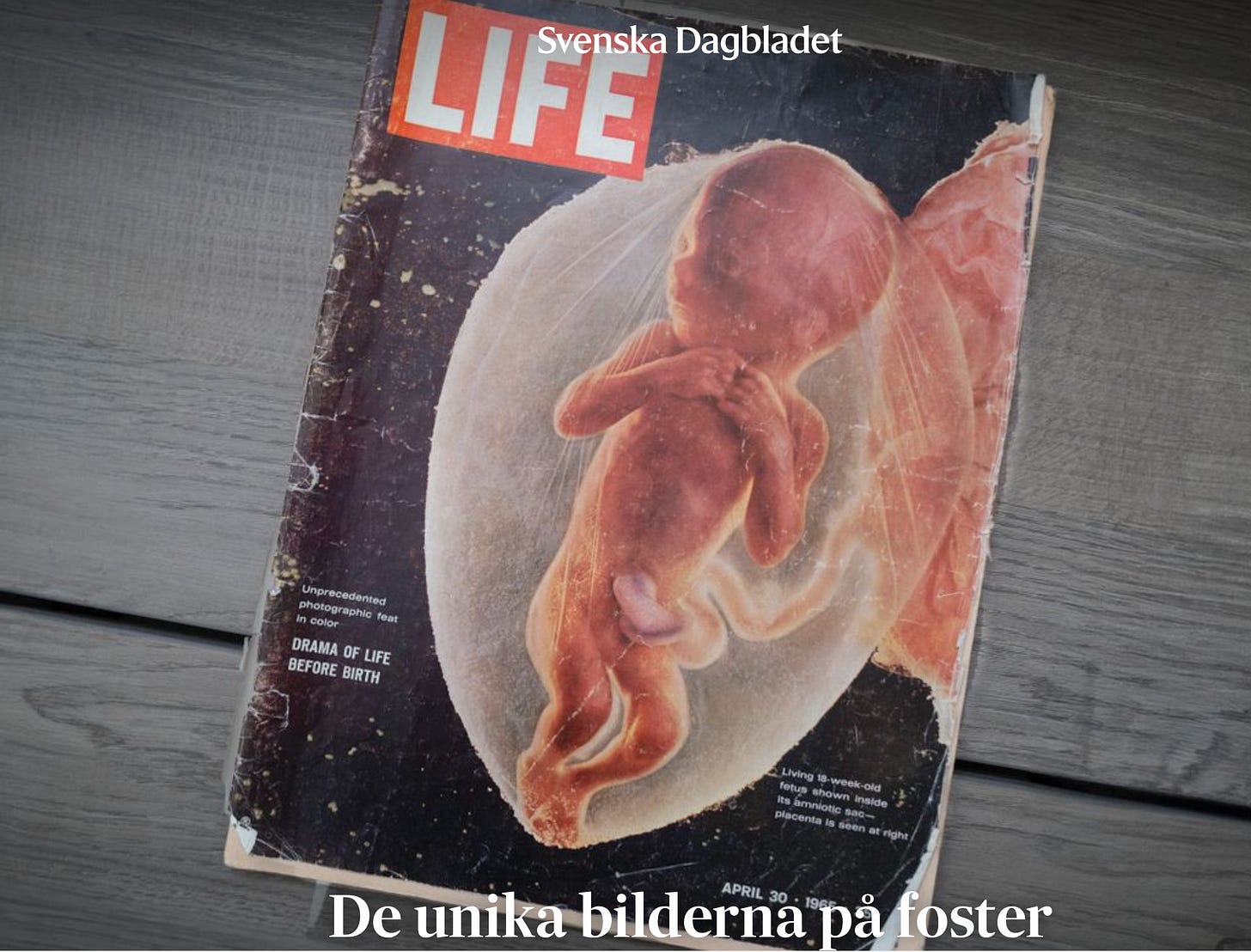

In 1965, the Lennart Nilsson issue of LIFE sold 8 million copies in four days.

The books of course, were published by the illustrious Bonniers publishing house. Did they indicate…in the book? Apparently, it is revealed in some footnotes, even in LIFE, that “some” of the images were of aborted fetuses.

I went back and looked at interviews with Nilsson, and sure enough: When proper photography questions were asked: “How did you get those photos…” he waffled, became evasive, and finally offered an answer that rattled off some technical photographic terms.

The question is: Why didn’t photographers expose him sooner?

Here’s Wikipedia:

“In an interview published by PBS, Nilsson explained how he obtained photographs of living fetuses during medical procedures including laparoscopy and amniocentesis and discussed how he was able to light the inside of the mother's womb. Describing a shoot that took place during a surgical procedure in Göteborg, he stated, "The fetus was moving, not really sucking its thumb, but it was moving and you could see everything—heartbeats and umbilical cord and so on. It was extremely beautiful, really beautiful!" Nilsson also acknowledged obtaining human embryos from women's clinics in Sweden.[7]The University of Cambridge claims that "Nilsson actually photographed abortus material... working with dead embryos allowed Nilsson to experiment with lighting, background and positions, such as placing the thumb into the fetus' mouth. But the origin of the pictures was rarely mentioned, even by anti-abortion activists, who in the 1970s appropriated these icons."[8] However, Nilsson himself has offered additional explanations for the sources of his photographs in other interviews, stating that he at times used embryos that had been miscarried due to extra-uterine or ectopic pregnancies.”

I’ve listened, twice, to the astonishing article in SVD about Nilsson’s stepdaughter who’s come clean now, to her immense credit.

I did, in truth, always wonder how Nilsson got those photos, and rather like the Apollo Mission—why didn't anybody follow after, with this magical technique? Why didn't it break down the doors of in utero photography?

Could it be that only some were aborted, while some really were alive and gestating?

I conclude no.

Think about it.

Nilsson either figured out how to light up and photograph inside a pregnant woman’s uterus, safely, or, he did not. If any of those shots were taken in vats, lit up from several directions—they they all were. Or none were.

That’s my hypothesis.

And I believe they execute the principle of “hiding in plain sight,” also known as “lesser magic.” You can find it in the footnotes, but nobody would say A Child Is Born , by some measures the biggest selling photography book in history, did not present itself as a a book of photographs of living, gestating babies.

Hence, it is also a story of fraud, of almost incomprehensible magnitude. It implicates not only Nilsson, but Bonniers, the Karolinska Institute, and the Nobel committee.

Below is the first half—Part 1— my translation and transcription of Lindh’s article. The writer unveils the story carefully, so we can adapt to the various complexities.

Part 1: The Heartbreaking Truth About Lennart Nilsson’s “A Child Is Born” Book—The Top Selling Photography Book In History, As Told By His Archivist And Stepdaughter, To SVD (My Subhead)

“My name is Kristina Lindh and I write for SVD’s Culture section. This article I am about to read is about the photographer Lennart Nilsson. His unique images of embryos that seemed to float dreamlike in the womb made him world famous. But how they actually came to be has been kept in the dark. Now his stepdaughter Anne Fjällstom has decided to reveal everything. Here comes the article:

“Now we part the curtain. We have decided to be totally open. Behind an anonymous metal door on Vanadisplan, Anne Fjällstom sits leaning forward on her chair. Her shirt is white and her cheeks, red. For two hours, she has been speaking about things she never spoke about in public before.

“Nobody has known how the photographs came to be, including myself. That has been the heaviest. To feel that I in fact also partook in this lie. SVD is the first newspaper to be given access to the archives with the original photographs of the embryos and fetuses, those that have been seen by millions of newspapers readers, that have shown the way for expectant parents for generations.

Imagesthat have been attached to countless protest signs on the other side of the Atlantic….that were sent out by NASA in a time capsule as a greeting from earth to alien civilizations. Now, for the first time, the archives are finally being examined, and organized. Negatives that have been in plastic bags for decades, or carefully placed in cabinets with the years marked. One hundred thousand prints from the 1940s and forward.

Next to Anne Fjällstom sits Solveig Gyllers, PhD in the History of Ideas. Just one year ago the two were enemies. They were on opposite sides of the war about the history of the one of photography’s giants. Now they are sitting together in a cooperative mission: The truth about Lennart Nilsson’s photos.

“This is a story that casts both shadow and light over the master photographer—for sure. But even more about the history of the progressive country in the north. These pictures would not have been able to be created anywhere else in the world.

A magnifying machine rests on a bench.

From the early 1980s until his death in 2017, this was where Lennart Nilssons had his dark room. The more advanced the equipment has been donated to the Karolinska Institute, which in turn donated it to the Technical Museum. The handheld Hasselblad cameras were sold to a collector who runs a photography museum in Vienna. But the cabinets are still here —the ones that they were used for some of the embryo photo shoots— so are the magazines from the over years, featuring Lennart Nilsson, which he saved over the years, Swedish Se, magazine, for example, and the American magazine Life.

“Before Lennart’s death, it was impossible to get anything organized,” says Anne Fjällstrom. “He was always focused on the next project and completely disinterested in organizing the archives. At the same time, he did not want to throw anything away. I have found taxi receipts from the 1940s.”

For almost 35 years, Lennart Nilsson was Fjällstrom’s stepfather. For 40 years, he has been in her life, or as she herself puts it, “I have been busy with Lennart since I was 18.” That was when her mother started a relationship with the famous photographer. The family devoted each Saturday to sorting negatives. Since 2001, Anne Fjällstrom has been responsible for Lennart Nilsson’s photo archives. She has put on exhibits and curated books. She has overseen digital and publishing rights.

“I took an overnight apartment in the old town,” says Anne Fjällstrom. “That was horrific. I was constantly working. I sometimes went over there in my pajamas.”

Now she lives further away.

For many years, the work was strictly associated with pride.

Lennart’s photo expedition to capture the polar bears in the Arctic, or his series about midwives in Lapland all achieved the status of classics. And his photographs of embryos and fetuses were a continual international sensation. “He was an icon,” says Anne Fjellström. “Untouchable.”

But a few years after the turn of century, the pendulum began to swing. It began to be discussed how the embryo photos came to be. That they were used earlier in the context of criticism of abortion was known. But that the photos were based upon aborted fetuses was less discussed. The pink shimmering spines that awakened such awe —was it, in fact, not life captured from inside the women’s stomachs?

Many felt personally duped and betrayed. Others felt upset on a moral level. “From being seen as a giant of Swedish photography, respect for Lennart Nilssons to a large degree disappeared, because of all this. That he photographed dead fetuses,” says Anne Fjällstrom. “It became the only thing people talked about.”

As a result: A family placed in suspended confusion, and a stepdaughter who wondered what was the point of being an archivist for a cultural icon whose reputation had become blackened.

The family today is comprised of Lennart Nilsson’s widow, the 82 year old Katarina Nilsson, her children Anne and Tomas, and her three grandchildren. The son from Lennart Nilsson’s first marriage is deceased.

The person who has perhaps written the most advanced material about Lennart Nilsson is Solveig Gyllers, PhD in History of Ideas.

It was in 2010, when The Karolinska Institute celebrated its 200th anniversary, and Solveig Gyllers contributed text for one of the booklets, that Anne Fjellström noticed her.

There was dissonance right away.

Gyllers relays that she repeatedly reached out to Fjellström to request access to the archives.

“I was irritated at Solveig,”Fjellström admits. “I felt, ‘Can we really not talk about anything else when it comes to Lennart?’ “

“Besides, the archive was just pure chaos.”

One year ago, the answer finally came back: “Yes.”

“I finally felt, you know, we’re sitting here doing the same thing in two different places. Isn’t it high time we work together?”

Since then, there have been no restrictions on what Solveig may look at. This decision was agreed upon by the whole family, says Fjällström.

They bend over the light table. On the lit surface, the oldest negatives are arranged.

One of them is the first embryo Lennart Nilsson’s photographed, in 1952. The embryo is six weeks old. They’ve been standing here for months together, working on what they both call “the puzzle.”

Which negatives belong to which? Which negatives are connected to which publications?

There is a pattern; There always is. When Solveig Gyllers started to study Lennart Nilsson, she zoomed in on what she calls “the magic year,” 1965. That was when LIFE magazine published a photo of one of his photos, of an 18 week old fetus, seeming to float inside the womb. The issue sold out in just a few days. The same year, the book “A Child Is Born” came out.

“I figured that was where it all began,” Solveig Gyllers says.

Eventually, she understood, this could not possibly be right. But where were the true facts?

Both Karolinska Institute and Bonnier’s Publishing, the two main given sources, had purged their archives.

Instead, Gyllers turned to people who had worked with Lennart Nilsson, many of whom were still alive. A story began to emerge, of the stars, or factors, perfectly aligned in the decade of the 1950s, primarily three:

First of all, a market. Solveig Gyllers relays:

Starting already in the 1930s, the market for photographs exploded. Small cameras emerge, and the photographers leave their studios and begin to walk city streets. New photo magazines are born. There is a demand for medical subjects. Medicine is viewed as “modern life,” and you researcher and doctors start to become famous.

1940 Lennart Nilsson, barely 20, manages to establish himself as an “all around” photographer, and gets his foot in the door at several magazines.

The second factor is Swedish abortion laws. Abortion was legalized in 1938, but only is special cases. For example, if the fetus was believed to be afflicted by unwished for genetic factors. (Note: “Oönskade arvsanlag,” means “un-desired genetics”.) (!) Or if the woman’s life was in danger. In 1946, the law was expanded. Abortion was now permitted also for women if her life situation was so stressful that it could affect her health to have a baby. All of a sudden, many more women sought abortions.

“This created an enormous debate,” says Solveig Gyllers. “Especially the Church and the doctors were critical. One may think abortion is a straight line of history, but in the 1950s there was a tremendous anti-abortion sentiment and movement in Sweden that is forgotten today. And the gynecologists, they were the very last to accept the new more relaxed laws.”

When 30 year old Lennart Nilsson got the chance to photograph embryos at Sabbatsberg hospital, it happened at the very same time that several doctors wanted to argue against the new abortion laws.

“They wanted reporting about the laws,” Gyllers says.

By collaborating with them, Nilsson won their trust. The medical world, normally impossible for a journalist to gain access to, opened up for Lennart Nilsson.

The third factor—we can call it “usefulness”—Solveig Gyllers uses the term “moral economy” is this: Even if one wanted to prevent abortions, they were mandated by law. And if one was, as a doctor, mandated by the state to perform them, they figured they may as well use the “material” for research.

“This is the determining factor, if you want to understand the career of Lennart Nilsson,” says Solveig Gyllers.

There were virtually no countries where it was as easy to get an abortion as in Sweden.

It meant there was a surplus of embryos. A special committee was formed that pushed for research expansion from fetal tissue. It was in the time of Polio, and an international campaign to fight it was underway.

Which country would the the first tome come up with a vaccine? For this one needed fetal cells. In many countries, monkeys were used, but the monkeys were more expensive, and imported from India. In Sweden, the thinking was: It’s better, and cheaper, to use so called human material.

End of Part 1

(To be continued…)

Celia, I’ve been thinking lately how we are all WHERE we are for a reason. And we are here NOW for a reason. This often seems to me to be exponentially true for you. You are WHO you are and here for profound reasons. It is no wonder you sometimes feel a heavy weight in your life. Please take care and allow others to carry with you. 💜

The exploitation of these precious human beings for the photographer's own fame and monetary gain needs to be brought out into the light. Whatever the intention was by the photographer, the fact is he was exploiting dead babies for his own personal and monetary gain just like abortion exploits babies for personal and monetary gain. I remember watching a video (this was in the 80's) with these exact photos in it in sex education class in High School. After the video, the teacher then taught about abortion as being a completely reasonable and viable option. Sickening.